History

The history of the

Panama Canal goes back to 16th century. After realizing the riches

of Peru, Ecuador, and Asia, and counting the time it took the gold

to reach the ports of Spain, it was suggested c.1524 to Charles V,

that by cutting out a piece of land somewhere in Panama, the trips

would be made shorter and the risk of taking the treasures through

the isthmus would justify such an enterprise. A survey of the isthmus

was ordered and subsequently a working plan for a canal was drawn up

in 1529. The wars in Europe and the thirsts for the control of

kingdoms in the Mediterranean Sea simply put the project on

permanent hold.

In 1534 a Spanish official suggested a canal route close to that of

the now present canal. Later, several other plans for a canal were

suggested, but no action was taken. The Spanish government subsequently

abandoned its interest in the canal.

In the early 19th century, the books of the German scientist Alexander

von Humboldt revived interest in the project, and in 1819 the Spanish

government formally authorized the construction of a canal and the

creation of a company to build it. The discovery of gold in California

in 1848 and the rush of would-be miners stimulated Americas interest in

digging the canal

Various surveys were made between 1850 and 1875 showed that only two

routes were practical, the one across Panama and another across Nicaragua.

In 1876 an international company was organized; two years later it

obtained a concession from the Colombian government to dig a canal across

the isthmus. The international company failed, and in 1880 a French company

was organized by Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps, the builder of the Suez Canal.

In 1879, de Lesseps proposed a sea level canal through Panama. With the

success he had with the construction of the Suez Canal in Egypt just ten

years earlier, de Lesseps was confident he would complete the water circle

around the world.

Time and mileage would be dramatically reduced when travelling from the

Atlantic to the Pacific ocean or vice versa. For example, it would save

a total of 18,000 miles on a trip from New York to San Francisco.

Although de Lesseps was not an engineer, he was appointed chairman for the

construction of the Panama Canal. Upon taking charge, he organized an

International Congress to discuss several schemes for constructing a ship

canal. De Lesseps opted for a sea-level canal based on the construction of

the Suez Canal. He believed that if a sea-level canal worked when constructing

the Suez Canal, it must work for the Panama Canal.

In 1899 the US Congress created an Isthmian Canal Commission to examine the

possibilities of a Central American canal and to recommend a route. The

commission first decided on a route through Nicaragua, but later reversed

its decision. The Lesseps company offered its assets to the United States at

a price of $40 million. The United States and the new state of Panama signed

the Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty, by which the United States guaranteed the

independence of Panama and secured a perpetual lease on a 10-mile strip for

the canal. Panama was to be compensated by an initial payment of $10 million

and an annuity of $250,000, beginning in 1913. This strip is now known as the

Canal Zone.

The Construction

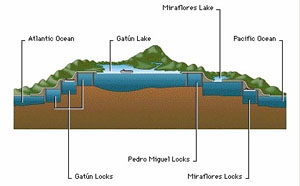

The length of the Panama Canal is approximately 51 miles. A trip along the canal from its Atlantic entrance would take you through a 7 mile dredged channel in Limón Bay. The canal then proceeds for a distance of 11.5 miles to the Gatun Locks. This series of three locks raise ships 26 metres to Gatun Lake. It continues south through a channel in Gatun Lake for 32 miles to Gamboa, where the Culebra Cut begins. This channel through the cut is 8 miles long and 150 metres wide. At the end of this cut are the locks at Pedro Miguel. The Pedro Miguel locks lower ships 9.4 metres to a lake which then takes you to the Miraflores Locks which lower ships 16 metres to sea level at the canals Pacific terminus in the bay of Panama. A pictorial view of the canals route can be seen below.

The Panama Canal was

constructed in two stages. The first between 1881 and 1888, being

the work carried out by the French company headed by de Lessop and

secondly the work by the Americans which eventually completed the

canals construction between 1904 and 1914.

The contract for the canals construction was signed on March 12th, 1881,

and it was agreed the work would be carried out for 512 million French

francs, but the contract was conditional in the sense it was not to become

binding until two years had elapsed.

During 1882 the excavation of the Culebra Cut was started, but due to the

lack of organization there were no tracks available to remove the spoil

that the excavators were producing. After the problems had been overcome,

the highest peaks of the cut were attacked. As work proceeded, the worry

of landslides and what slope should be adopted to avoid them became a major

concern.

In 1883 it was realised there was a tidal range of 20 feet at the Pacific,

whereas, the Atlantic range was only about 1 foot. It was concluded that this

difference in levels would be a danger to navigation. It was proposed that a

tidal lock should be constructed at Panama to preserve the level from there to

Colon. This plan would save about 10 million cubic metres of excavation.

The French company started to run into financial difficulties during 1885 and

even applied to the French government to issue lottery bonds, as this had been

successful during the construction of the Suez canal when that project was

at the point of failure through lack of money. Rumours of these difficulties

caused increased interest within the American government.

A report made by the Americans in 1886 noted that housing for the workforce

was under construction and a great deal of plant was available. Unfortunately

the plant required to construct the canal was is in short supply, there were

too few dredgers, the French excavators were too light and were stopped by

large boulders and too much work was being done by hand. The turnover of the

labour force was immense, as the men wanted to return home to spend the savings

they had accumulated and because of the inadequate medical care that was

available.

It was realised that the solution to all the problems encountered, was that

the construction of a high-level lock canal would reduce an enormous volume

of excavation and prevent the landslides.

The abandonment of the scheme at this stage would cause financial ruin for

all the investors and a severe blow to the French. It was suggested that the

original plan should be modified and the lock system should be employed.

Eventually, in 1899 the French attempt at constructing the Panama Canal was

seen to be a failure. However, they had excavated a total of 59.75 million

cubic metres which included 14.255 million cubic metres from the Culebra Cut.

This lowered the peak by 102 metres. The value of work completed by the French

was about $25 million. When the French left, they left behind a considerable

amount of machinery housing and a hospital. The reasons behind the French failing

to complete the project were due to disease carrying mosquitos and the inadequacy

of their machinery.

The construction of the canal was recommenced by the Americans in 1904. The first

step on the agenda was to improve the standard of living and ensure ill health

would be a thing of the past.

The first American steam shovel started work on the Culebra cut on 11th November 1904.

By December 1905 there were 2,600 men at work in the Culebra cut.

Sidings and tracks for the spoil wagons had been laid, the dredging at both the

Atlantic and Pacific portions of the canal were being carried out and a survey

of the area for the largest dam along the canal had been started.

It wasn't until June 1906 that the decision on type of canal was decided. It was

to be a lock canal. This would enable the River Chagres to form a lake.

Peak excavation within the Culebra cut exceeded 512,500 cubic metres of material

in the first three months of 1907 and the total workforce exceeded 39,000. The

rock was broken up by dynamite, of which up to 4,535,000 killogrammes were used

every year.

The plant used in the Culebra cut included in excess of 100 Bucyrus steam shovels

each capable of excavating approximately 920 cubic metres in an eight-hour day, a

picture of a typical steam shovel is shown below.

More than 4,000 wagons were

used for the removal of the excavated material. Each wagon was capable of

carrying 15 cubic metres of material. These wagons were hauled by

160 locomotives and unloaded by 30 Lidgerwood unloaders.

The full extent of the excavations carried out by both the French and Americans

is shown in a longitudinal section from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans is shown

below.

Problems at the Culebra Cut

When the canal was first

designed, the problem of landslides had been ignored. Slides of earth

and more importantly rock, increased the amount of excavation within

Culebra. The cross section of the canal was constantly being changed

to accommodate for the landslides. The slides caused the upper edge of

the cut to be taken back beyond their original lines. The original design

for the banks comprised a series of narrow benches which acted as rock

catchers, alternating with short steep slopes. It was first decided by

the International Board of Consulting Engineers that the rock would

be stable at a slope of 1 in 1.5, it was also stated the rock had the

strength to stand at a height of 73.5 metres at 1 in 1.5. In fact the

rock began to collapse from that slope at a height of only 19.5 metres.

Numerous test borings had been carried out and samples of the rock were

taken, therefore, the quality of the rock was known. The reason for the

misjudgement of the strength was due to the underlying strata which contained

bands of clay and iron pyrites. The iron pyrites seemed to cause the problems,

as it is liable to oxidize when exposed to the air and moisture, with the

result that the rock would disintegrate. Therefore, when the overlying

material had been removed, rainwater precipitated through to the lower

strata which included the pyrites, whereby rapid deterioration occurred.

The first major slide occurred in 1907 at Cucaracha. The initial crack was

first noted on October 4th, 1907, then without warning approximately 382,000

cubic metres of clay, moved more than 4 metres in 24 hours. This slide caused

many people to suggest the construction of the Panama Canal would be impossible.

The clay was too soft to be excavated by the steam shovels and was eventually

removed by sluicing with water from a high level.

The Cucuracha slide was to become a problem again in 1913, when it crossed the

cut until it reached the opposite bank. The steam shovels excavated the slide

as it was moving and eventually won the battle. A picture of the Cucaracha slide

is shown in figure 4 below.

Further movements were

experienced at the base of the cut, including the sudden upheaval of the

ground at the middle and a sinking of the ground in other areas. These

movements were caused by the pressure of the rock, which seemed to flow

as soil and not having the typical behaviour of rock. This problem was

overcome by removing material from the upper levels of the cut thus,

reducing the pressure.

As a direct result of all the slides and upheavals encountered, excavation

increased by 15.3 million cubic metres. This was about 25% of the total

estimated amount of earth moved.

The slides which were encountered didn't cause any delay in the progress

of the canal, as this was determined by the speed at which the locks were

constructed.

Many projects to enhance and widen the channels have been carried out since

the opening of the canal. The main area to receive these works has been the

Culebra Cut as numerous landslides have occurred and the need for two ships to pass.

The Locks

Along the route of the canal there is a series of 3 sets of locks, the Gatun,

Pedro Miguel and the Miraflores locks.

At Gatun there are 2 parallel sets of locks each consisting of 3 flights.

This set of locks lift ships a total of 26 metres. The locks are constructed

from concrete from which the aggregate originated from the excavated rock at

Culebra. The excavated rock was crushed and then used as aggregate. In excess

of 1.53 million cubic metres of concrete was used in the construction of the

Gatun locks alone.

Gatun Locks:

Initially the locks at Gatun had been designed as 28.5 metres wide. In 1908 the

United States Navy requested that the locks should be increased to have a width

of at least 36 metres. This would allow for the passage of US naval ships. Eventually

a compromise was made and the locks were to be constructed to a width of 33 metres.

Each lock is 300 metres long with the walls ranging in thickness from 15 metres at

the base to 3 metres at the top. The central wall between the parallel locks at

Gatun has a thickness of 18 metres and stands in excess of 24 metres in height.

The lock gates are made from steel and measures an average of 2 metres thick, 19.5

metres in length and stand 20 metres in height.

In 1912, when Colonel Geothals, the American designer of the Panama Canal,

visited the Kiel Canal, he was told the canal should have been built 36 metres

in width, but by then it was too late. The locks can be seen during construction

below. A general picture of the Gatun locks can be seen below.

The smallest set of locks along the

Panama Canal are at Pedro Miguel and have one flight which raise or lower ships

10 metres. The Miraflores locks have two flights with a combined lift or decent

of 16.5 metres.

Miraflores Locks:

Both the single flight of locks at Pedro Miguel and the twin flights at Miraflores

are constructed and operated in a similar method as the Gatun locks, but with

differing dimensions.

The Dams

Many engineering aspects of the

Panama Canal point out the concern for the protection of the environment and

natural resources.

As the excavations were being carried out, an enormous amount of excess soil

was produced. The French initially hauled the soil to an adjacent valley where

the soil was dumped and allowed to build up. This itself caused many problems

during the rainy season and was the cause behind many of the landslides.

When the Americans started work on the canal, the engineers decided to reuse

this soil for the building of the Gatun dam. This dam held back the water from

the Chagres River and thus creating the Gatun Lake. As time passed, the soil

would continue to settle thus, increasing the strength of the dam.

The dam itself is 1.5 miles in length and is nearly 0.5 mile wide at its base.

The construction of the dam involved constructing 2 walls along its length using

the excavated rock from the Culebra cut. The space between these 2 walls was then

built up with impervious clay. This clay gradually dried and hardened into a solid

mass almost equal to concrete in its water-resistant properties. This dam contains

16.9 million cubic metres of rock and clay, equivalent to about one tenth of the

entire excavation of the canal.

The dams at Pedro Miguel and Miraflores are small in comparison to Gatun. Their

foundations are on solid rock and are subjected to a head of water of 12 metres,

whereas the Gatun dam is subjected to a 24 metre head.

The dam at Pedro Miguel is an earth dam approximately 300 metres in length with

a concrete core wall.

At Miraflores there are two dams forming a small lake with an area of about 2

square miles. One of the dams is constructed of earth and is 210 metres in length.

The second of the dams at Miraflores is 150 metres in length and is made from

concrete.

The Future

The ships for which the canal was

designed are now long gone. Modern shipping has increased the size of ships.

The increase in the tonnage in which can be carried has thus caused problems

for the canal. The canal can only accommodate ships carrying up to 65,000 tons

of cargo, but recently ships which are able to carry 300,000 tons have been

introduced.

The problem of the ever-increasing size in ships has caused discussion into the

construction of a new canal joining the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. There have

been discussions on three alternative routes for a new canal, through; Columbia,

Mexico and Nicaragua. The Columbian and Mexican routes would allow for the

construction of a sea level canal, whereas the Nicaraguan route would require a

lock system.

If a replacement canal were to be constructed, the economic effect on the Republic

of Panama would be a great concern as the present canal employs 14,000 people, of

which 4,000 are Panamanians. It has been suggested that, if a new canal were to be

built, the existing canal could be converted to a hydroelectric power station at a

relatively small cost. As Panama has no iron-ore deposits and lacks oil, natural

gas resources or skilled labour, there is no real need for a new source of cheap

power.

The capacity of the existing canal could be increased by converting it to a sea

level passage. This would be carried out by the dredging of more than 765 million

cubic metres of earth and rock which could be carried out without interfering with

existing canal traffic. Water retaining structures would be constructed to maintain

the canal levels during excavation. When excavation had been completed, the water

retaining structure would be demolished by blasting them into deep pits. The lowering

of the canals level would take place over a seven day period and would be the only

time traffic would be disrupted.

It was suggested during the 1960's that the canal could be increased in size by

the use of nuclear explosives and would cost less than one third, and take about

half the time than using conventional excavation methods. It is now obvious that

this would cause a great deal of concern for all anti-nuclear groups.

The Panama Canal has been under the control of Panama since the year 2000.

Conclusion

What makes the Panama Canal remarkable

is its self sufficiency. The dam at Gatun, is able to generate the electricity to

run all the motors which operate the canal as well as the locomotives in charge of

towing the ships through the canal. No force is required to adjust the water level

between the locks except gravity. As the lock operates, the water simply flows into

the locks from the lakes or flows out to the sea level channels. The canal also

relies on the overabundant rainfall of the area to compensate for the loss of the

52 million gallons of fresh water consumed during each crossing

Despite the limit in ship size, the canal is still one of the most highly travelled

waterways in the world, handling over 12,000 ships per year. The 51-mile crossing

takes about nine hours to complete, an immense time saving when compared with

rounding the tip of South America.

Until the early 1970's the Panama Canal Company made considerable profits. After

a period of nearly 60 years the loss in profit required the increase of tolls 3

times in 4 years. Much of the equipment, some of which dates back to 1914, now

requires expensive modifications, simply to continue moving its present rate of

traffic.

The original plan for the Panama Canal was evolved from many years of engineering

study; unfortunately, it had not been based on marine operating experience.

Bibliography

1 Barrett, J. The Panama Canal, what it is, what it means. 1913.

2 Hammond & Lewin. The Panama Canal. 1966.

3 LaFeber, W. The Panama Canal, The crisis in historical perspective. 1978.